Ystalyfera

History and Heritage

Ystalyfera Historian Noel Watkins

I have mentioned my mentor and fellow researcher Mr. (David) Noel Watkins. I met him a few years ago when I was researching the life of James Palmer Budd, (the manager and co owner of the Ystalyfera Iron Works), and I was finding it difficult to sort out all the different mines, levels, drifts etc which have been opened, worked and abandoned throughout the Swansea Valley.

Noel would have been the first to agree that a researcher should research something which at least holds his/her interest, and although he knew I was passionate about "my cemeteries" he could never quite understand why I would spend so many hours IN A CEMETERY, cutting away undergrowth just to find a name or two. On the other hand, when he would pull out his vast collection of mining maps and spend an hour or two explaining the different veins of coal to be found in each colliery, I knew as a geologist, he was lost in his world. Although it was interesting I always wanted to know more about the miners and owners than the actual process of hauling black gold from the interior of the earth and so we begged to differ, but our friendship was mutual in the fact that we believed history should if not able to be preserved at least be written down.

When he knew he was unwell and unable to write on his computer, he would prefer to come in the car and have me drive to places where he could show me where old buildings once stood and never knowing where his memories would take us, I often had to say to my husband I'll be back sometime. I remember him pointing out the old water troughs in Ystalyfera where the horses had drunk from when pulling their carts and suddenly we were in Clydach taking photographs of the fountain and trough which had been removed from the bottom of the Cottage Hospital, due I believe to the public outcry of the smell of the stagnant water. Other times we drove over to Graig y nos, the Cray Reservoir, Crynant and Seven Sisters in order for me to see the Roman Road and of course the collieries but always with one aim in mind to impart his knowledge and to widen my horizon.

I only knew Noel a handful of years before I had to say goodbye but I could see just how many dedicated years of research he had added to his rich source of knowledge and expertise in his own field. When I used to question why had he not written a book or something I was always sad to hear him reply I did not have the schooling and the computer was so new that the facts have remained in my head.

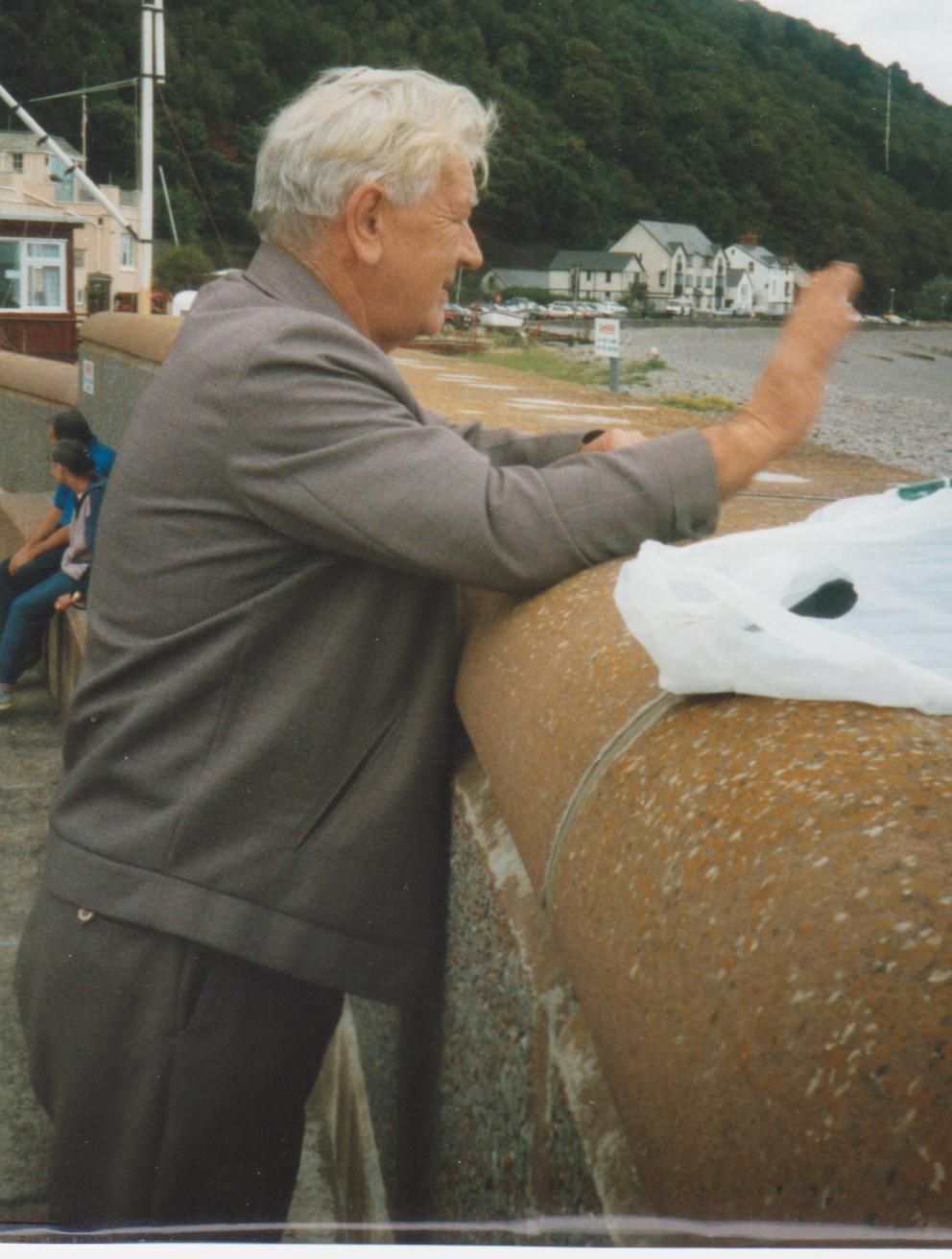

With Noel's death in 2007, YEARGROUP had lost its 10th member and I suppose now, looking back, I should not be surprised that I folded for at least three months afterwards. I could no longer pick up the telephone by the side of my desk when ever I had uncovered something which I knew would be of interest to him and I could not bring myself to go through my notes for a while without a feeling of sadness and loss of a friend. I have taken two photographs of Noel one, when he was laying a wreath at the Ystalyfera War Memorial and the other when we went off to Callwen Churchyard in search of the memorial stone for the pilots who crashed on the mountain. A third photograph he gave me before he entered hospital and told me to remember that when he had gone he "would be waving down to remind me to continue as a researcher". I hope I have done just that and in fact the other day I did find some thing which Noel had had printed, his interview with South Wales Evening Post.

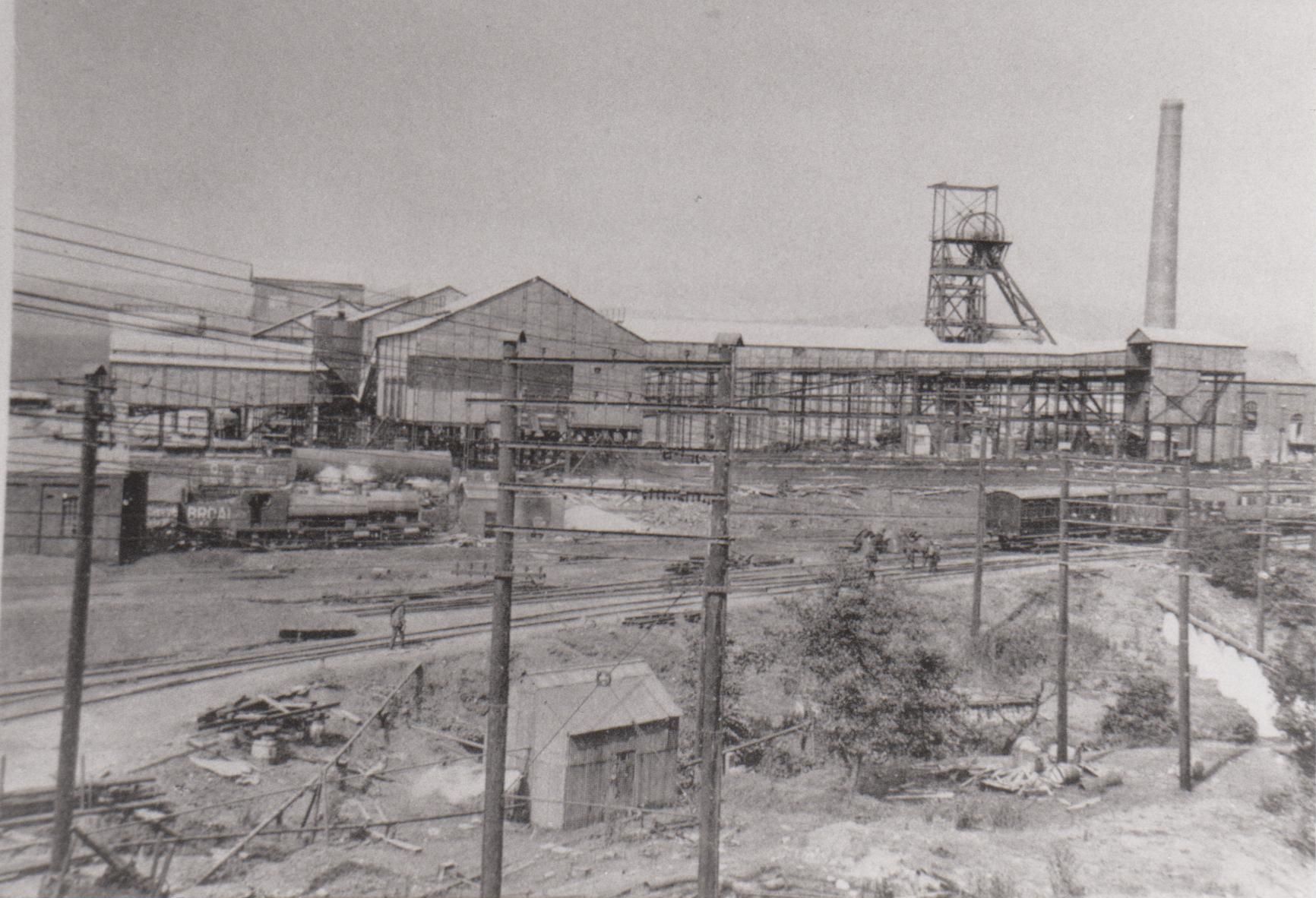

Val TrevallionBelow is an article by Noel Watkins, from 1994, on the hard life of local miners:-

*The Photographs used in this article were purchased by YEARGROUP from a car boot sale. They were being sold as part of a collection by Mr. John Jones of Ammanford who informed me that he was no longer able to continue with his hobby and the photographs have been used for illustrations in various books.

*The photographs of Noel belong to me Val Trevallion

Ystalyfera - South Wales

History Articles

- Tree Felling 2018

- Fe, Fi and Fo - Baby Sparrows

- Eyesores of Ystalyfera

- Blooming Ystalyfera

- Lost Landmarks of Ystalyfera

- Ystalyfera Then and Now

- Our Feathered Friends

- Ystalyfera Swimming Pool

- Pantteg Murder

- British Legion, Ystalyfera

- Bronchitis Valley

- Ystalyfera Cemeteries

- Storm Damage

- Cemetery Damage

- A Sacred Promise

- Historian Noel Watkins

- Yan Boogie - Eileen Baker

- Dangerous Bridges

- Interesting Snippets

- Jewish Cemetery, Swansea

Ystalyfera History

Email Yeargroup:

yeargroup@hotmail.co.uk

Email Wolfian Design:

webdesign@wolfianpress.com